Filmmakers were using dyes, stencils, baths, and tints as early as the late-19th century.

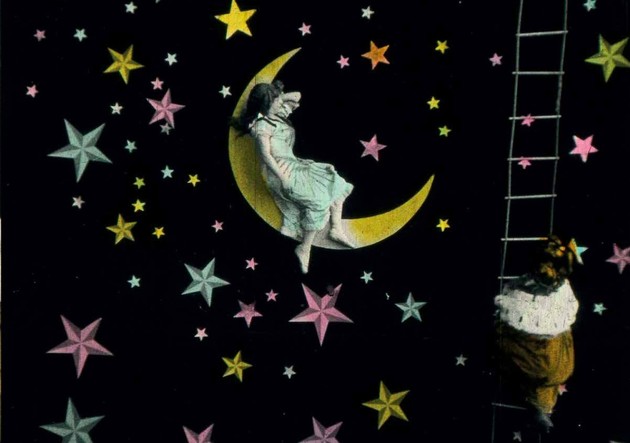

June 25, 2015For many modern audiences, silent films are virtually synonymous with black and white. Yet as far back as 1895, more than 80 percent of them were all or somewhat colored with dyes, stencils, color baths, and tints. These additives and techniques transformed an already magical medium into transcendent dreamscapes that were colored by craftspeople—mostly women—who painted every tiny black-and-white frame one-by-one, prefiguring the colorization process developed in the 1970s. Archived at Holland’s EYE Filmmuseum, more than 250 still images culled from 96 of these largely forgotten films are featured in an eye-popping new book, Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema.

Early color films, particularly fantasies, were widely screened in theaters during the silent era for both artistic and practical reasons. “Artistically, the fantasy genre was quite suited for elaborate coloring in that colorful costumes and special effects was widely associated with successful stage genres of the day,” says one of the book’s authors, Joshua Yumibe. Fantasy was also adapted early for film, beginning in the late 1890s by pioneering filmmaker Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902). For practical reasons, says Yumibe: “It was easier for audiences to accept color in fantasy films as the aniline dyes used were fairly bright and spectacular—like the colors associated with the féerie stage genre and also with fairground attractions: colors that were meant to grab and dazzle one’s eyes.”

Dance films also had a following. The hand-coloring of these films was designed to emulate magical stage effects in which colored lights would be projected onto the robes of the dancers while they performed. There are a few spectacular examples of this in the book—Les Parisiennes (1897) for example. Other types of films that were colored during the period included Lumière nonfiction films of blacksmiths and backyard card games.

Along with Yumibe, a film historian and associate professor at Michigan State University, the other co-authors are Tom Gunning, a scholar of film history and theory, whose idea was to make a picture book to spotlight the treasure trove of early color images that comprised silent cinema before World War I, the heyday of hand coloring; Giovanna Fossati, chief curator of the EYE Filmmuseum and professor of film heritage and digital film culture at the University of Amsterdam; and Jonathon Rosen a painter, illustrator, and animator, who designed the book with Laura Lindgren. Martin Scorsese wrote the foreword.

The images were distilled from 2,568 reference photos that were photographed by Yumibe directly from projected prints. Most were “safety prints,” since films were printed on nitrate bases until the 1950s, made from nitrate cellulose, a volatile and highly flammable material developed in the 19th century for explosives. “Though dangerous, it was also extremely malleable and moldable and inexpensive,” Yumibe explains, “[It was] the first modern plastic, which led to its eventual adoption in a range of products—dolls, jewelry, buttons, and at the end of the nineteenth century as the base of film.” When stored in temperature controlled rooms however, he notes, the film has a long shelf-life.

The EYE Film Institute in the Netherlands, which has a state-of-the-art preservation facility, provided the nitrate prints they used for the project. The authors wanted to get as close to the originals as possible to reproduce the colors and content of the frames and using contemporary, mostly digital tools to reproduce the nitrate-analog frames. “This of course isn’t a perfect system either … but we’re really happy with the relative, chromatic fidelity we were able to capture and reproduce in the book,” Yumibe says.

The book’s designers, Rosen and Lindgren, arguably created two formats. The first section is a textbook history of the genre. The second is the 200-page, full-bleed image section organized into thematic groupings, including The Dream, The Fairytale, Metamorphosis, The Voyage, and a final section called Fancy. “The endpapers are meant to evoke the experience of gazing at the nitrate film strips draped on the light box at the Amsterdam Film Institute Archival storage facility,” Rosen says. The ending or postscript is a fully annotated and illustrated section of thumbnails edited by Elif Rongen which Rosen notes, lays out the credits and adds an extra visual flourish.

The book also sheds light on pioneering directors such as Méliès, Gaston Velle, and Segundo de Chomón. While Méliès is fairly well known, in part thanks to Scorsese’s film Hugo (2011), Velle and Chomón, who both worked for the production company Pathé during these years, are much less so, even though they built upon Méliès’s success and innovated color films. Chomón began his career in film as a colorist, and in 1905 he was recruited by Pathé as one of its chief directors, where he oversaw the company’s trick and fairy genres. His wife Julienne Mathieu, with whom he often collaborated, was a film actor and also colorist.

Until recently, however, archivists and preservationists thought color was an add-on that didn’t necessarily need to be preserved: “This is particularly the case for films that were tinted and toned, as stencil and hand-colored films were often seen as being something special,” Yumibe says. But there were also technical reasons for this lack of preservation: Chromogenic film stocks such as Eastman Color had very poor shelf-lives—they faded quickly, and it wasn’t cost-effective to preserve these films.

This has led to the popular assumption that many of our silent classic films were in black and white, when in fact originally they were often elaborately tinted and toned. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) for instance is a film that was known for generations as being in black and white until it was restored in color,” Yumibe says. So Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema is an essential book—for its gorgeous array of stills, but also because it offers a reminder of how audiences were being dazzled by the magic of color movies long before the color revolution in cinema.