On the eve of the American Revolution, more than one-quarter of those living in the 13 colonies were not free. The majority of this group were African Americans enduring lives of unpaid labour, a product of the Atlantic slave trade. A smaller but still substantial group was indentured servants: Europeans sold and transported to the colonies under contract. The American Revolution did not directly challenge either of these practices – but its focus on liberty and natural rights raised many questions about their place and future in the new nation.

ContentsThe forced relocation of Africans to America is a long, often tragic story that starts with the Atlantic slave trade. The kidnapping and sale of humans into slavery was widespread on the African continent long before European settlement in America. The march of Europeans into Africa in the 1500s only allowed the slave trade to expand globally.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to purchase slaves in Africa and transport them to what is now Brazil. Unpaid labour was a valuable asset when constructing colonial settlements, so the trade flourished and was soon picked up by the British, French, Spanish and others.

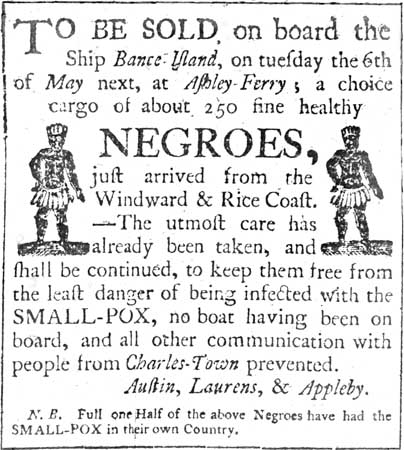

Over time, trading African slaves grew into a flourishing industry of its own. Slaving companies established bases and ports in West Africa, purchased slaves from African traders, then transported them across the Atlantic for sale in the New World. The demand for labour in America was so high that strong male slaves were sold at significant prices, creating lucrative profit margins.

African slaves were not the first group forcibly transported to America, however. Until around 1700, the vast majority of unpaid work in the colonies was performed by indentured servants. Indeed, indentured servants comprised more than half the European migration to North America during this period.

Indentured servitude was a form of contracted slavery common in Britain in the 17th and 18th centuries. It took several different forms but most individuals were forced into indentured service by non-payment of debts. This was often forced upon them by a court, the alternative being a sentence in a debtors’ prison. Criminals, political dissidents, prisoners of war and the homeless were also often forced into indentureship.

An indenture was, in simple terms, a contract binding the individual to perform unpaid labour for a fixed period, usually several years. When this time had elapsed, they were granted freedom. Indentures became assets and could be bought, sold and traded – those who purchased an indenture then acquired the individual bound by it.

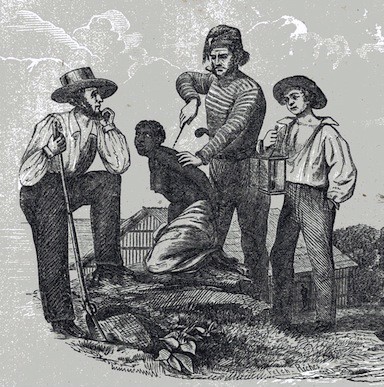

In general, European indentured workers received better treatment from their masters than African American slaves. Nevertheless, indentured workers enjoyed very little freedom. They performed long and arduous forms of work and were often subject to physical punishments like flogging.

As mentioned above, the numbers of indentured servants in the first century of colonial settlement was high. This was particularly true in the southern colonies, where indentured workers made up around three-quarters of all European settlers before 1700.

The purchase of indentures was sometimes used to alleviate a shortage of women in some areas. It was not uncommon for the indentures of young females to fetch a higher price than those of males. Indentured women were generally acquired as domestic servants. Many suffered mistreatment, such as excessive punishments and sexual abuse. Under the terms of the contract, if a woman fell pregnant, her indenture was often extended by two years.

A common indenture of the period was this contract applying to Ann Hill, a Scottish teenager:

“This indenture, made at Edinburgh on the 28th day of April 1733, betwixt [between] David Ferguson, merchant on the one part and Ann Hill… on the other part. Witness that the said Ann Hill does covenant and agree that David Ferguson and his assignees for the space of four years [from] her first and next arrival at Philadelphia or any of His Majesty’s plantations in America, there to serve David Ferguson and his assignees in what service and employment they shall think fit to assign her during the space foresaid… The said David Hill does covenant and agree to pay for the said Ann Hill, her passage to Philadelphia, and to find for and allow her meat, drink, apparel, lodging and all other necessaries…”

The first arrival of African slaves in the 13 colonies can be traced back to 1619 when a passing slave ship, en route to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, landed in Virginia. Locals there were desperate for labourers to work large plantations, so purchased a number of Africans under indenture.

As Virginia and its neighbouring colonies expanded and claimed large tracts of land, the demand for slave labour grew accordingly. Ships sailing from Africa, packed like sardines with human cargo, began to bypass their usual routes to the Caribbean and sail for the British colonies in North American.

From their perspective, this capture, transportation and sale into slavery much have been terrifying. The cargo holds of Atlantic slave ships were packed to bursting, often housing hundreds of people in small spaces. Many slaves were chained to plank beds, others shackled to walls, masts or each other. Few slaves were given room to move or access to sunlight. Leaking decks and no sewage meant that slave holds were soon awash with water and human waste.

The voyage across the Atlantic could take between four and six weeks. Unsurprisingly, many slave ships were decimated by diseases like dysentery, as well as malnutrition, heat, humidity, fighting and mistreatment from the crew. Those who died on passage were simply tossed overboard, their loss written off as a taxable expense.

African American slaves were unevenly distributed across the 13 colonies. By 1770, there were approximately 460,000 slaves across British North America but more than 350,000 of them lived in the southern colonies.

Virginia had more than 185,000 slaves, or around 40 per cent of its total population. Other colonies with large numbers of slaves were South Carolina (75,000, 55 per cent), North Carolina (68,000, 33 per cent), Maryland (63,000, 30 per cent), New York (19,000, 12 per cent) and Georgia (15,000, 75 per cent). Another 30,000 or so slaves were spread across the remaining seven colonies.

There were clear reasons for this skewed distribution. The southern economy was largely based on crops grown for sale and profit rather than subsistence – specifically, tobacco, rice and indigo, a plant used to produce blue dyes. Growing, nurturing and harvesting these crops was labour intensive but the southern colonies, in comparison to their neighours to the north, were thinly populated.

Slaves could still be found in the northern colonies, albeit in much smaller numbers. In the north, slaves were less likely to be used as agricultural labour. They were mostly found in larger cities working as general labourers in construction or on roads, as haulers on the docks, as artisans or as domestic servants. Some colonies, such as Rhode Island, had few slaves of its own but continued to profit heavily from the slave trade that passed through its ports.

The life, treatment and conditions of African American slaves is well known. While stories of slaves being well treated and cared for have been recorded, most endured lives of backbreaking unpaid work and degradation, their schedules, conditions and treatment almost entirely at the whims of their masters.

Once purchased, slave became the chattels or personal property of his or her owner. They were denied rights, freedom of movement and choice, and education. They required the master’s permission to marry or have children. Like indentured servants, slaves could be bought and sold as demand required, even if this meant separating family groups.

Most slaves worked six-day weeks, often from dawn to dusk. Disobedience, slacking and escape attempts were usually met with harsh punishments. Beating, whipping and branding of slaves was not uncommon. They were required to grow crops for subsistence, usually in their own time, and were often afflicated by European diseases to which they carried no resistance or immunity.

In addition, many female slaves were subject to sexual abuse from their male owner or members of their family or staff. This was done either for their satisfaction, as an act of humiliation or for economic reasons, to increase slave holdings (children born to enslaved females inherited their status). Some kept female slaves as concubines, though usually covertly, interracial unions being taboo in white colonial society.

At the time of the revolution, most wealthy colonial planters and gentlemen owned at least a few slaves. Several who went on to play significant roles in the revolution were themselves slave owners. Of the 55 who attended the 1787 constitutional convention in Philadelphia, 17 delegates owned a total of about 1,400 slaves.

George Washington was a prolific slave owner until his death. At the age of 11, Washington inherited 10 slaves from his father. On his marriage to the widowed Martha Custis, Washington inherited almost 300 more. At the time of his death in 1799, there were 316 slaves working at Mount Vernon.

Thomas Jefferson, despite routinely voicing criticism of slavery and the slave trade, maintained around 200 slaves at Monticello during the revolutionary period. Later DNA evidence suggests that Jefferson, late in his life, fathered several children with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, though the nature of their relationship is unknown.

Among the other Founding Fathers who owned slaves were Patrick Henry (112 slaves at the time of his death), James Madison, the architect of the Bill of Rights (36 slaves), Richard Henry Lee, John Jay, John Hancock and Benjamin Rush.

Benjamin Franklin owned several slaves until the 1780s and profited from the sale of advertisements to slave traders. He took two male slaves to England as personal servants in 1757, one of whom absconded. Franklin changed his position towards the end of the revolution, publicly opposing the practice of slavery and, in 1787, becoming president of one of the first abolitionist societies.

“Though the issue grew to divide the country, slavery did not have to be squarely faced while the colonies were part of a mother country that tolerated it… However for the slave-centered South even the possibility of this change was enough to light the spark for the coming revolution. This came with the Somerset decision in England, that freed a slave brought to London by a colonist, raising a question as to slavery’s legitimacy in the Empire. Although this decision did not overturn slavery in the colonies, its logic was not lost on southerners. For the South, compromise on slavery was unthinkable. Independence was the only solution.”

Alfred Blumrosen, historian

1. At the beginning of the American Revolution there were almost 450,000 African American slaves in colonial America, most working in the agrarian-dependent southern colonies.

2. Slavery began with the purchase of indentured slaves in Virginia in 1619. By the end of the 17th century, slave populations could be found in all 13 British colonies.

3. The system of enslavement used in America was chattel slavery, where slaves were traded, bought and sold, then treated as the personal property of their masters.

4. While conditions varied, most African American slaves endured a miserable existence and were subject to heavy workloads, strict restrictions, punishments and mistreatment.

5. Thousands of Europeans also arrived in America as indentured servants bound to long terms of unpaid labour, usually for defaulting on debts. Indentured servants were also treated poorly, though unlike African Americans they were usually granted their freedom.